Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza: Why Not a 3-State Solution?

Or, Why We Need a Path to TWO New Palestinian States

A little more than a month ago, the Knesset (i.e., the Israeli parliament) voted “resoundingly against unilateral Palestinian state recognition.” Unfortunately—and by almost every measure—Israeli skepticism about a two-state solution has not diminished since then.

For many within the international community, the current Israeli position has significantly dampened hopes for a post-war permanent peace settlement. Some have called attempts to secure a pathway to a Palestinian state a “two-state mirage.” In its wake, these experts have suggested the Biden Administration “[focus] on dealing with the situation as it is,” and try to use its power in Israel to secure Palestinian rights in the Israeli-occupied territories. Others, like The New York Times’s Bret Stephens, have instead advocated for the creation of “an Arab Mandate for Palestine,” which would have “[t]he (very) long-term ambition…[of turning] Gaza [and all of Palestine] into a Mediterranean version of [cosmopolitan] Dubai.”

Yet, in response to all this, I ask a much simpler question: if not 2-state, why not 3-state? Why not a path to two independent Palestinian states instead of one?

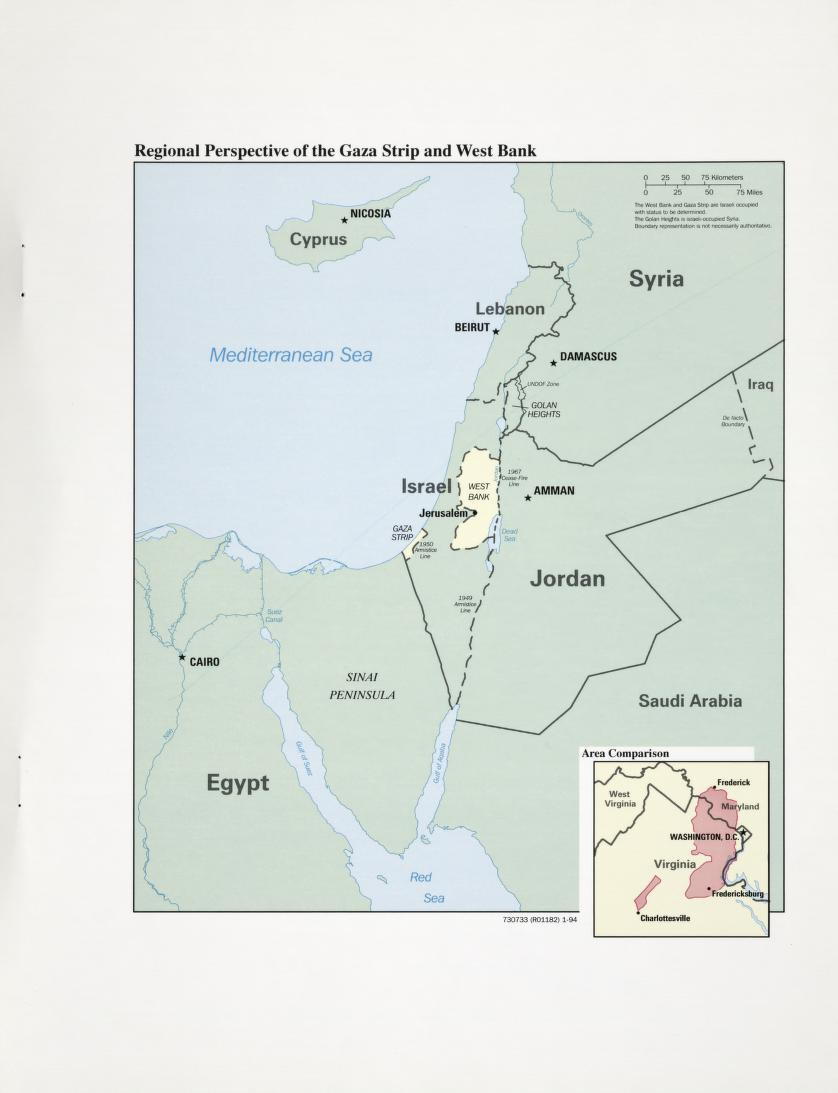

Consider this map of Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza:

As you can see, a truly workable two-state solution would require a relatively extensive “land corridor” between the West Bank and Gaza. Let us—just for a second—set aside the concerns Israel would have about the establishment of such a corridor within what was before Israeli territory. Exactly how effectively would a government like this work in the first place?

Similar arrangements have failed in the past. Take the example of Bangladesh:

Bangladesh was originally a part of what we could call “greater Pakistan.” Now, granted, there was no land corridor between “West Pakistan” and “East Pakistan” established immediately after the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan. The problem, however, was much deeper than that: while West and East Pakistan “shared [the] dominant religion of Islam,” they “were very different in terms of language, ethnicity, and culture.”

In other words, they were two different Muslim peoples separated from each other by the wide gulf of India. Uniting the two of them under one common government was thus that much harder, if not impossible. Ultimately, these two separate peoples decided to take two separate paths: in 1971, East Pakistan secured its independence from West Pakistan at the end of the Bangladesh Liberation War.

A unified Palestine would arguably face many of the same difficulties. Yes, the cultural differences between the West Bank and Gaza may seem much less difficult to bridge. But are they really? As it stands now, the West Bank and Gaza are currently under the control of two very different governments. Consequently, the West Bank and Gaza have had two very different experiences of Israel and Israelis. One area has Israeli settlers, the other does not. One area has ever-present Israeli outposts and checkpoints, the other does not. One has faced a blockade, the other has not. One has faced one of the most intense aerial bombardment campaigns of the century, the other has not. And so on and so on and so on.

These two very different experiences will eventually create two very different Palestinian identities—no matter what happens when the war ends. At any rate, the center of political power in Palestine will continue to shift towards the West Bank (for obvious reasons). That may very well become something that many Gazans would come to resent, even in the unlikely event of an immediate version of a two-state solution. Again, these types of differences will make the West Bank-Gazan geographical divide all the more important.

There is also another factor at play here. One of the Arab “point men” on Palestinian policy has been a Palestinian exile named Mohammed Dahlan. In the past, Dahlan has been said to have “a wide network of support in Gaza.” As of mid-February, he has consulted with senior Hamas officials, and “[hinted] that the group could be persuaded to give up control [of Gaza] as part of a broader package that created a Palestinian state” (emphasis mine).

But Dahlan, as it happens, is also a part of a broader network actively “seeking to unseat” Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas. Dahlan is not alone in his dislike of Mr. Abbas. Many in the international community have called on Abbas to step down in favor of newer and more popular leadership in the West Bank and perhaps greater Palestine.

Still, any plan to replace Abbas and transform the Palestinian Authority requires Abbas’s cooperation. And Abbas and his allies would be unlikely to support a plan that catapults Dahlan back into West Bank politics. Especially since Abbas is immensely unpopular and may even be vulnerable to corruption charges. Abbas would almost surely oppose any government in the West Bank which did not 1) offer him a chance to rehabilitate his image and 2) protect him from criminal investigations. Which means any unified Palestinian government with Dahlan in its coalition is (we can only assume) a non-starter.

A Gazan government created with the help of Dahlan and separate from the West Bank, on the other hand, offers a much easier framework for a permanent settlement between Israel and Greater Palestine. And although it would indirectly address legitimate Israeli security concerns, it is by no means a concession to Israel. It is simply a concession to the geographical reality.

Netanyahu once said that “maintaining the separation between the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza would prevent the establishment of [any] Palestinian state.” Let us prove him wrong by trying to establish two viable Palestinian states in the place of one. Let us show him that one region’s path to statehood need not be an obstacle to the other’s.

As I have said before, time is running out. Netanyahu’s radical right-wing government is expanding settlements at a record pace, including in once-dismantled settlement areas like Homesh. Eventually, the Israeli settler population will overwhelm the West Bank—and become a much more formidable population there. If that happens, say goodbye to any permanent peaceful settlement. The conflicts such a situation could create in the West Bank might make 1990s Rwanda “look like a children’s birthday party” (to borrow the words of Thomas Friedman).

There is a good amount of work to do on the Palestinian side, but it can be done. According to the Gallup of Palestinian polls, Palestinian support for Hamas has dropped eleven points since December. Support for armed groups “to provide local protection in the West Bank” has dropped fifteen points. Accompanying that is increasing Palestinian approval of both nonviolence and negotiators.

My fellow progressives, all this is what it will take to “give Palestinians a voice,” and to give Israelis lasting security under their own vine and fig tree. We are at an inflection point. Look around you. As we speak people like Trump’s son-in-law and former “envoy for Middle East peace” Jared Kushner are already talking about building “valuable waterfront property” on the seafronts of Gaza. With the blood still fresh on the ground.

We have a clear choice to make. Tens of thousands of Palestinians and approximately a thousand Israelis should not die for nothing. They should not have died at all, but they should not die for nothing. They should not have suffered so that the cycle of violence continues on as if nothing happened, or so that Jared Kushner can make a handsome profit off the Gaza real estate market.

That is why now is the time for not a one, not a two, but a three-state solution.